Can a flyover be anti-fascist?

The imperial politics of elevated roads, from Mussolini's Rome to the Silvertown Way

It’s September 1934. A Thursday afternoon, fine and warm. We’re standing on a newly built concrete flyover in Silvertown, on London’s eastern outskirts at the docks. It’s crowded, and the streets around are festooned with flags and paper flowers.

After a while, the crowd hushes and everybody cranes their necks to see what’s happening. Leslie Hore-Belisha, the Minister of Transport, cuts a white ribbon stretched across the carriageway, then pulls a cord to reveal a plaque bearing the new road’s name: Silvertown Way. He shouts to the crowd, “I declare this approach to the London Docks open to the King’s subjects for their free use for ever.”1

Then, we go to the nearby Stratford Town Hall for speeches. Hore-Belisha refers to Mussolini’s recent opening of Rome’s Via dell’ Impero—the Imperial Road. “A fine dream,” the minister says, which “only a dictatorship could make true.” Then he says, “Silvertown Way is the conception and the achievement of Democracy. Silvertown Way is surely as bold an undertaking as the Imperial Road of Rome.”2

Gut-spinners and the refuse of Tartarus

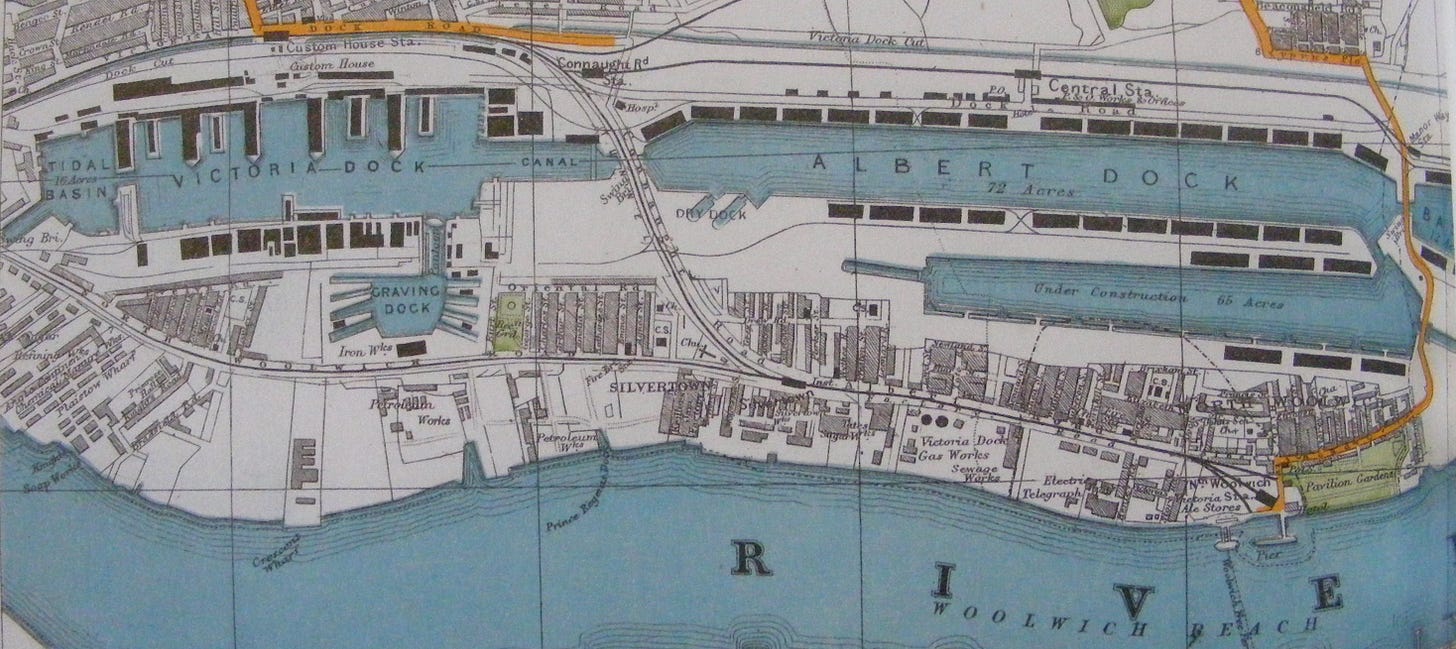

Let’s start with why the Silvertown flyover got built. The vast Royal Docks complex was constructed between the 1840s and the 1920s on previously deserted, low-lying marshland. First came the Royal Victoria Dock, now with the Excel exhibition centre alongside it. Then the Royal Albert dock was built farther east. Finally, in the 1920s, the King George V dock completed the set. London City Airport now sits between the latter two.

Besides the Royal Docks themselves, countless factories sprang up along the riverfront, housing noxious trades ousted from London proper by the 1844 Metropolitan Building Act.

In 1857, Charles Dickens called Silvertown “a place of refuge for offensive trade establishments turned out of town—those of oil-boilers, gut-spinners, varnish-makers, printer’s ink-makers and the like.”3

Whereas Henry Tomlinson, writing nearly 80 years later, described the area as “a perplexity of railway sidings, roads that wander and lose themselves, creeks intruding among backyards, cemeteries, gasometers, the funnels of steamers mixed with factory chimneys, warehouses built of the refuse of Tartarus, and a formless spread of the grey homes of those who, somehow, must supply the reason for its existence.”4

Some of the bigger firms included the Thames Iron Works, Brunner Mond, the Silver rubber works (hence Silvertown) and Henry Tate’s sugar works, as well as railway and telegraph works and a huge gasworks in nearby Beckton.

An efficient transport network to serve such a dense assemblage of industrial and port facilities was vital. But by the early twentieth century, Silvertown’s roads hadn’t been expanded to meet ever-increasing demand brought by increased trade and the rise of motorized goods vehicles. In 1920, a senior transport official said that Silvertown had “congested roads carrying probably the heaviest traffic in the world.”5

It wasn’t just delays to vans and lorries that was hampering trade. Pedestrian holdups, at busy intersections and railway crossings, was causing factory employees to be chronically late.

The solution? A wide concrete flyover to carry the goods and workers of empire right over the congested streets below.

The Silvertown flyover

It was completed in 1934. It was an early British example of a grade-separated urban flyover, an elevated road passing over not just a single river, road, canal or railway (as in a bridge or simple viaduct) but over an entire ground-level transport network in a crowded city location.

In the United States, engineers had started building double-deck or viaducted urban streets such as Wacker Drive in Chicago, or streets with grade-separated interchanges like the Bronx River Parkway in New York, in the 1920s. But these early schemes didn’t match the scale or complexity of the Silvertown scheme.

And it was democratic. Five years after the Silvertown flyover opened, Charles Bressey, its chief engineer said, “It is to the credit of this viaduct that from it, travellers gain a fascinating view, never before vouchsafed to them, of docks and shipping which are invisible from the streets at ground-level. Viaducts are so often and so thoughtlessly denounced as destructive of beauty that we do well to remember the refreshing and hitherto unsuspected views they may reveal.”6

The comments he made there came after the publication of his report into London’s 30-year transport needs. We can discern a light bulb switching on in the mind of this transport engineer: that London could be transformed by building for it a new motor road network, but one that was literally laid over the old—just like the flyover at Silvertown.

Bressey, like many urban planner-engineers, had long lamented the perceived failure of Christopher Wren to rebuild London after the seventeenth-century great fire on a grid system. In a film to publicise his report, Bressey describes Wren’s abortive scheme as “a plan so enlightened, so far-seeing, that it would even have met the needs of modern traffic.”7 Instead, the streets had remained unaltered—an opportunity lost—and the result, Bressey claims in the film, is congestion.

The voiceover remarks, “Quick transport is essential to trade. Trade is London’s life. Congestion strangles it. But there is a way to ease this congestion. Just as Wren made a plan for seventeenth-century Londoners, so Sir Charles Bressey has worked out a plan for us.”

Bressey is then seen looking down from a lofty office window onto the congested streets below, before placing a series of transparent overlay sheets onto a map of London, each sheet showing parts of his proposed new road network encircling and crossing the city.

He describes how his roads would cross each other and intersect with the existing street pattern in Central London by using grade-separation—effectively a giant lattice of flyovers, like Silvertown’s. He gestures to a series of dramatic visual depictions of aerial cityscapes. Then he says, “We must build elevated highways on viaducts ... we must drive tunnels under obstacles ... we must have roundabouts and flyovers of the most modern type ... we must adopt every device for facilitating the movement of traffic and giving it the clearest possible course.”

Concrete and empire

There was something more to Silvertown’s flyover than its form. There was its material: reinforced concrete. And here, we start to see empires come more closely into focus.

In 1926, one concrete engineer had reported that “The general public is gradually being educated into the many uses of reinforced concrete, and everyone is now well acquainted with this material, which is considered as a symbol of strength and durability.”8

This description—a symbol of strength and durability—could equally apply to the British Empire, or rather the representation of it current in British culture at that time.

In 1935, the travel essayist Henry Tomlinson (we met him earlier talking about the “refuse of Tartarus”) narrated a fictional visit of a “venturer” by train to the docks at Silvertown. He wrote, “The miles of concrete quays, as he walks eastward to Gallions Station for a train back to town, will tell him more of Empire than all the exhibitions. For there are ports and ports. London is more than a seaport. It is a world market.”9

Silvertown Way and other concrete structures at the Royal Docks appeared more real than the concrete exhibition halls on the other side of the city in Wembley, built for the British Empire Exhibition of 1924–5 to allow visitors to “inspect the Empire from end to end.” It was the docks in east London that were the true heart of the British Empire.

Imperial roads in the Fascist Age

Politicians knew the power of imperial rhetoric when it came to infrastructure projects. In 1926, as the proposed new flyover was debated in the House of Commons, the trade unionist and Labour MP for Silvertown, Jack Jones, had stated that “it is not a road for West Ham, it is not even a road for London, it is a road to the Empire.”10 The following year, he made an even more bombastic proclamation, as reported in The Guardian:

“Mr Jack Jones made a speech in the mock big bow-wow style on behalf of the projected road to the London Victoria Dock. ‘Not a mere arterial road,’ he said, swelling his breast and raising high his head, ‘but an imperial road that Caesar would have gloried in.’ He was half-serious, but he could not resist the temptation to talk in the towering way of the real Imperialists, and when he had finished he joined heartily in the general laughter which his little piece of burlesque had provoked.”11

He was more than half-serious. In the months leading up to the completion of the flyover scheme, there was a lot of bickering about what it should be called. Suggestions included “King George V Avenue,” “Prince of Wales Avenue,” or simply “London Dock Road.” By September 1934 the name still hadn’t been decided.

Then on 7 September, the Ministry of Transport’s Deputy Chief Engineer wrote to Minister Leslie Hore-Belisha to say that “Enquiries have been made from all sources in London concerning the Via-Dell’-Impero at Rome and a note is attached, giving the available information, together with a sketch illustrating the road.”12

The Via dell’ Impero, or Imperial Road, was opened by the Italian fascist leader Benito Mussolini in 1932 ostensibly to reduce traffic congestion, but more significantly as a ceremonial avenue designed to bring Rome’s ancient imperial past into view. It wasn’t elevated, like the Silvertown flyover. But it did create similar views from above: from its sidewalks, passers-by could look down into carefully framed excavations of ancient Roman remains.

When he opened the road, Mussolini stated that, “we must create the monumental Rome of the twentieth century. Rome must be a city worthy of its own glory. And this glory must be renewed incessantly so as to hand it down to future generations as the heritage of the Fascist Age.”13

A prominent Italian archaeologist noted that the Via dell’ Impero was not just an archaeological or aesthetic project, but “a street necessitated by the traffic requirements of the modern city ... a modern street which also endeavours to give value to the remains of the Imperial Forums and monuments, to give a panoramic view of them.” He concluded that, whilst it was a Roman road, it was “no less an Italian road, the road of a modern nation, which joins modern initiative to the cult of her past.”14

We saw earlier how Transport Minister Leslie Hore-Belisha picked up on Jack Jones’s imperial rhetoric in his speech following the ribbon-cutting on the flyover, when he said, “Silvertown Way is the conception and the achievement of Democracy. Silvertown Way is surely as bold an undertaking as the Imperial Road of Rome.”

Then he expanded on his theme. “Not only is there about it an equally fine touch of imagination, but it has the advantage of serving an even more practical purpose. It exposes to view not the ruins of the past, but a vision of our present maritime greatness. Till now the London Docks have been hidden from sight. This road gives a perspective of them, so that all who use it may see the masts of those ships which carry our commerce. This thing has been done by the people, by the so-called common men and women who had the idea, who have made the road a worthy outlet to the world.”15

This is the crucial point. It was imperialism, but democratic. He said, “The London Docks are no exception to the general rule that docks and wharves are usually hidden behind high walls which shut them out of public view ... The new road, with its bridges and its viaduct, will allow Londoners, and visitors to London, to gain a far-flung view of the waterways, docks and wharves which represent the real foundation of London’s wealth. This is the Aladdin’s Cave of London, and a thousand years of the romance of its commerce, wealth and industry are reflected in the scenes that are visible from these new viewpoints.”16

It is hard to overstate the significance of this vision. The geographers Felix Driver and David Gilbert have said this: “The ebb and flow of goods at the docks determined the fortunes of hundreds of thousands of working-class people; there was in this sense no more significant site in the landscape of empire.” Many visitors to the area were incoming sailors or immigrant workers. Driver and Gilbert noted that “For many, the first sight of London was of the vast and strange dockland landscape, on a ship sailing up the Thames estuary.”17

But this first vision of the heart of empire wasn’t always a good one. Albert Linney, chronicler of London’s River Thames, described the old Victoria Dock Road in Silvertown as being “as wretched a street as could be found in London ... What an impression of the Capital of the British Empire must have been given to foreign seamen emerging from the Royal Victoria Dock into London!” He went on, “Every time I walked down that road … I was appalled at the squalor of the scene.”18

Labourite imperialism

The Silvertown flyover was meant to change all that. We should see it as an expression of a new imperialism—of free trade, an empire built on the circulation of people and goods, and by the opening up of the empire to the public view. This 1930s episode was an expression of modern democracy versus modern dictatorship.

And in many ways it was a distinctly Labourite expression. Jack Jones, the Labour MP for Silvertown, had set out the Labour view of imperialism in his memoirs written in 1928. He characterized his party’s policy as one based on ideas of self-government, especially in India, against the Tory “govern and control” approach. Labour wanted to encourage an India along the lines of Canada and Australia—“a free, independent, completely self-governing part of the Commonwealth of Nations which we call the Empire.”19

Labour’s imperial policy, Jones stated, was “to trust the people on the spot; to develop self-government wherever possible; to repeal unfair treaties; to be truly democratic in foreign relationships.” His party, he said, “will abolish all artificial barriers, make intercourse free between peoples, in the firm belief that increase of knowledge of people and things is increase of understanding. Labour will endeavour to increase cheapness of transport and travel and abolish irritating restrictions.”

The anti-fascist flyover that nobody sees

The Silvertown flyover is still there. You can visit and explore it, as I have done countless times. It’s easy to miss, not like the huge post-war flyovers in the west of the capital, or in cities across the UK. It’s modest; mundane almost. Today, it doesn’t really go anywhere, and the streets it flies over are rarely congested. The docks are closed and the factories, for the most part, gone.

But when you look under its skin you find a very different story—the story I’ve presented here. In 1930s Britain it was offered as a national statement of democracy at a time of rising fascism in mainland Europe. The British Empire might have been beginning its decline, but it was stronger in cultural terms then than it had been in the Victorian period.

But the discourse at the time was about reform of the empire—reform from within—and the idea of imperialism was fused with ideas of progress and modernity, with emphasis placed on machines and efficiency. The home city of the British Empire was London, but it had to work well, like a machine.

The Silvertown road scheme, with its concrete flyover, was unlike any other road building scheme in London in the interwar period. Unlike arterial roads being constructed at the time, this was about freight rather than private transport; it was about the working classes rather than the middle and upper; it was about industry rather than leisure; and it took place in a cramped, congested, urban streetscape rather than over virgin agricultural lands.

In an editorial published on the day the Silvertown Way was opened, The Times made this claim: “The Victoria Dock Road and the road from Cairo to the Cape are as much parts of the same highway as were the Via Flaminia and Watling Street in the days of the Roman Empire; and those who see to-day the magnificent sweep of the new road will agree that the modern engineer is no whit inferior to the classical in his conception of what the beginning of an Imperial highway ought to be.”20

As the Silvertown Way flew over junctions and crossings, it presented a distinctly modern and democratic imperial vision, looking out and forward, in contrast with Mussolini’s fascist Imperial Road, which looked back to an ancient past. Silvertown was a reinforced-concrete graft onto the empire’s congested old heart. It was a vision in which new technologies—concrete and the internal combustion engine—could enable the building of a new city, a city of the future, an empire of the future.

***

Next time, I think I’ll talk about how to read a flyover. It’ll be fun. You’ll want to subscribe, if you haven’t done so already, to be sure you don’t miss it…

The Sphere, 22 September 1934, 424.

The Times, 14 September 1934, 9.

Charles Dickens, “Londoners over the Border,” Household Words: A Weekly Journal 16, no. 390 (12 September 1857): 241.

Henry Tomlinson, Below London Bridge (London: Cassell, 1934), 38.

The Times, 20 April 1920, 11.

Charles Bressey, “Greater London Highway Development Survey: Discussion,” The Geographical Journal 94, no. 5 (November 1939): 356.

GPO Film Unit, The City: A Film Talk by Sir Charles Bressey [film], 1939.

G. C. Workman, in “Twenty-First Anniversary Number,” Concrete and Constructional Engineering 21, no. 1 (January 1926).

Almey St John Adcock, ed., Wonderful London: Silver Jubilee Edition (London: The Amalgamated Press, 1935), 61.

Hansard, HC Deb 14 July 1926, vol 198 c542.

The Guardian, 6 July 1927, 4.

The National Archives: MT 39/389, memorandum, Frederick Cook to Leslie Hore-Belisha, 7 September 1934.

“The Via Dell’ Impero and the Imperial Fora,” The Builder, 23 March 1934, 496.

Ibid., 503 and 505.

The Times, 14 September 1934, 9.

The National Archives: MT 39/389, ‘Victoria Dock Road: Notes for the Minister’s Speech’ (no date).

Felix Driver and David Gilbert, “Heart of Empire? Landscape, Space and Performance in Imperial London,” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 16 (1998): 21.

The PLA Monthly, November 1934, 6.

Jack Jones, My Lively Life (London: John Long, 1928), 181–91.

The Times, 13 September 1934, 11.